Check this out.

My favorite part is "...this could lead to chronic renal failure and he could lose a kidney..."

I tap on the UpToDate icon to launch Safari and go straight to UpToDate. The icon is called a webclip. You can learn more about this at this Apple webpage.

I tap on the UpToDate icon to launch Safari and go straight to UpToDate. The icon is called a webclip. You can learn more about this at this Apple webpage.

Then you arrive at a manuscript that reads great on the iPhone screen.

Then you arrive at a manuscript that reads great on the iPhone screen.

Clinical Course and Treatment

In the Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services now includes a diagnosis of HIVAN as an indication for ART, regardless of CD4 count.(94) Other treatment options that may influence the course of HIVAN include angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and corticosteroids administered before dialysis or kidney transplantation.

Antiretroviral Therapy

The original case reports of HIVAN described a rapid and inexorable progression to ESRD over a period of weeks to months.(2-4) However, after highly active ART came into use, several dramatic reports of renal recovery among these patients emerged in the medical literature. In one study, a patient with HIVAN and dialysis-dependent renal failure became dialysis free after 15 weeks of ART. Repeat renal biopsy revealed significant histologic recovery from fibrosis with only infrequent glomeruli showing mild collapse and minimal fibrosis.(65) Since then, a growing number of studies has helped establish ART as a first-line treatment for HIVAN.

The effect of ART on kidney disease progression has been characterized primarily by observational studies. A cohort of 53 patients with biopsy-proven HIVAN from the Johns Hopkins renal clinic was found to have better renal survival when treated with ART compared with patients who did not receive ART (adjusted hazard ratio: 0.30; 95% CI: 0.09-0.98).(95) In a retrospective study of 19 patients with a clinical diagnosis of HIVAN, after median follow-up of 16.6 months, the use of protease inhibitors was significantly associated with a slowing of the decline in creatinine clearance.(96)

In the Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy (SMART) study, 5,472 HIV-infected patients who had a CD4 count of >350 cells/µL were randomly assigned to continuous or episodic use of ART and were followed for a mean period of 16 months. Investigators found that, compared with continuous ART, planned treatment interruptions guided by CD4 counts significantly increased the risk of fatal or nonfatal ESRD (hazard ratio: 4.5; 95% CI: 1.0-20.9) in the treatment interruption arm. Although this study was not statistically powered to detect a difference in renal outcomes, the high incidence of ESRD in the treatment interruption group suggests that continuous therapy with antiretroviral medications is a key factor in preventing and slowing progression of kidney disease.(97)

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors

Both ACEIs and angiotensin II receptor blockade have inhibited the development and progression of HIVAN in animal models.(98-100) Two prospective studies support the use of ACEI for the treatment of HIVAN. In a case-control study of 18 patients with HIVAN prior to the advent of ART, 9 were treated with captopril, and matched with 9 controls.(101) The captopril-treated group had improved renal survival, defined as time to ESRD, compared with controls (mean renal survival: 156 ± 71 days vs 37 ± 5 days; p < .002). In a single-center, prospective cohort study of 44 patients with HIVAN, 28 patients received fosinopril 10 mg/day, and 16 patients who refused treatment were followed as controls over 5.1 years.(102) The median renal survival of treated patients was 16.0 months, with only 1 patient developing ESRD. All untreated patients rapidly progressed to ESRD over a median period of 4.9 months. Despite the limitations of these studies, they suggest that ACEIs may be beneficial in curbing progression of HIVAN, and this class of drugs is a reasonable first choice as an antihypertensive agent for patients with HIVAN.

Steroids

Evidence supporting the use of steroids for the treatment of HIVAN is also based on observational data.(95,103,104) In a single-center cohort study, 20 patients with HIVAN were prospectively enrolled to receive treatment with corticosteroids. Most patients (17 of 20) manifested improvements in kidney function and significant reductions in 24-hour urinary protein excretion. After steroid therapy, mean rates of protein loss declined from 9.1 ± 1.8 g per day to 3.2 ± 0.6 g per day (p < .005).(105) Another study of steroid therapy employed a control group and found similar results with no increased risk of infection in the steroid group.(104) Although these studies were generally limited by their nonrandomized designs, based on this evidence, steroids are considered second-line therapy for patients with HIVAN. The use of steroids should be considered for patients with a documented rapid deterioration in kidney function despite ART.

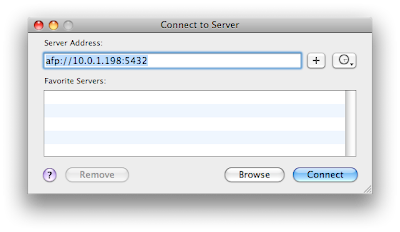

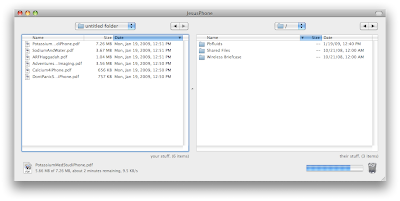

Enter the afp address listed at the bottom of the DataCase screen. Then connect. You should click on guest at the next dialog box.

Enter the afp address listed at the bottom of the DataCase screen. Then connect. You should click on guest at the next dialog box.

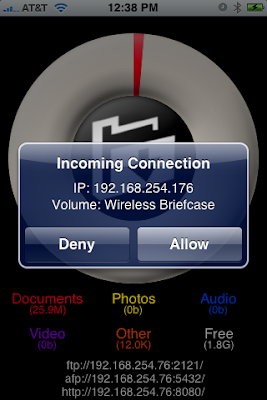

Select the folder you want and then accept the connection on the iPhone.

Select the folder you want and then accept the connection on the iPhone.

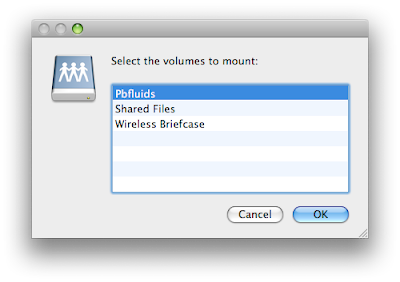

3. You then can select the volume yoiu want to look at. Volumes are like folders on your computer.

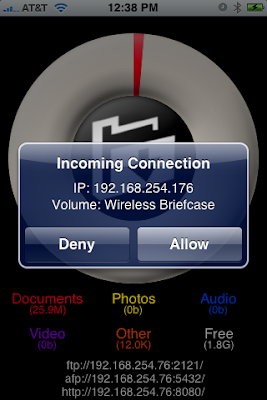

3. You then can select the volume yoiu want to look at. Volumes are like folders on your computer. When you select either of the above directories you will need to accept the connection on the iPhone. This provides some degree of security.

When you select either of the above directories you will need to accept the connection on the iPhone. This provides some degree of security.

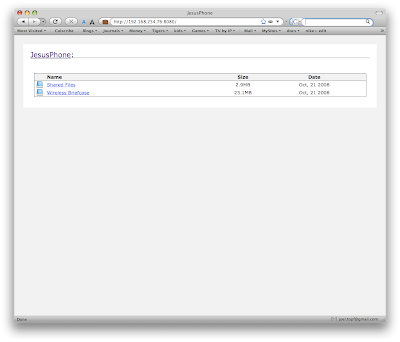

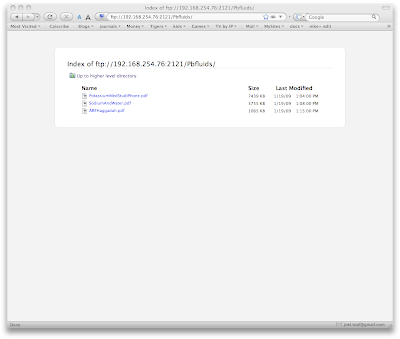

To upload the files, launch an FTP client. I use Transmit by Panic software. Enter the ftp address at the bottom of the DataCase home screen and drag the files you want over to the iPhone.

To upload the files, launch an FTP client. I use Transmit by Panic software. Enter the ftp address at the bottom of the DataCase home screen and drag the files you want over to the iPhone. You can view any of the files you uploaded on the iPhone right in the DataCase application.

You can view any of the files you uploaded on the iPhone right in the DataCase application.

Steven Fishbane, MD from The University of Pennsylvania, came to our fellowship program to discuss Fe and hemodialysis. He began by talking about hepcidin and then went on to discuss the iron targets in light of the DRIVE trial and then touched on IV Fe and proteinuria and finished with a discussion of platelets and mortality and its relationship to recent anemia trials.

Steven Fishbane, MD from The University of Pennsylvania, came to our fellowship program to discuss Fe and hemodialysis. He began by talking about hepcidin and then went on to discuss the iron targets in light of the DRIVE trial and then touched on IV Fe and proteinuria and finished with a discussion of platelets and mortality and its relationship to recent anemia trials.

The purpose of the DRIVE study and its six week extension, DRIVE II, was to determine the efficacy and safety of supplemental intravenous iron in anemic hemodialysis patients receiving recombinant erythropoietin who had a transferrin saturation <> 500 ng/mL. The intravenous iron group did increase their hemoglobin levels slightly more than control patients not given intravenous iron without additional toxicity, leading the authors to conclude that intravenous iron in this situation was both safe and effective. Unfortunately, the design and power of both studies were not sufficient for the investigators to reach these conclusions.First, the decision to increase the dose of recombinant erythropoietin in each group by 25 % confuses the response to ESA and iron. In a chronic inflammatory state, such as chronic renal disease, the problem is not impaired iron availability but insufficient erythropoietin, which is required to mobilize iron and upregulate transferrin receptor expression. It is well recognized that erythropoietin trumps hepcidin in this situation and the authors merely confirmed that phenomenon.

Second, in the control groups of both DRIVE and DRIVE II, there were a disproportionate number of women, who are more likely to be iron deficient, and their response to recombinant erythropoietin proved this, reducing the effectiveness of comparisons.

Third, both DRIVE and DRIVE II were open label observational studies and in addition physician discretion was also allowed with respect to erythropoietin dosing and iron administration. This discretion can introduce significant bias, weakening the conclusions of the studies.

Fourth, no attempt to estimate blood loss, iatrogenic or otherwise, was made for either experimental group. Fifth, the difference in the hemoglobin level achieved with supplemental iron was not striking and also pushed the hemoglobin level above that currently recommended for safety reasons. Finally, since the serum ferritin and transferrin saturation increased in the iron-supplemented group, a state of iron overload was achieved that was unnecessary and the 12 week observation period was certainly not long enough to exclude the possibility of iron-induced organ toxicity.

It is clear that more data derived from larger prospective trials that are conducted for longer periods are needed. Until this data becomes available, anemic hemodialysis patients not responding to conventional doses of recombinant erythropoietin, in whom the serum ferritin is greater than 500 ng/mL, should first be evaluated for a source of blood loss or infection. Then the patient should be given a higher dose of recombinant erythropoietin for a minimum of 6 weeks with serial transferrin saturation and ferritin measurements before resorting to intravenous iron supplementation.

Increased RBC push platelets along the walls of the blood vessel. So treatment may cause a lot of atherothrombotic complications because they have both more platelets and red cells.

Increased RBC push platelets along the walls of the blood vessel. So treatment may cause a lot of atherothrombotic complications because they have both more platelets and red cells.

Hi nephron!

Your presentation Diabetic Nephropathy is currently being showcased on the 'Health & Medicine' page by our editorial team.

It's likely to be there for the next 16-20 hours...

Cheers,

- the SlideShare team

30% are woman and 51% are US medical graduates. This is a decrease in the number of foreign medical grads from 50% in 1999 to 40% in 2005.

30% are woman and 51% are US medical graduates. This is a decrease in the number of foreign medical grads from 50% in 1999 to 40% in 2005. 757 applicants applied for 372 spots in at 135 accredited programs in 2007.

757 applicants applied for 372 spots in at 135 accredited programs in 2007. Nephrology is the fourth most popular internal medicine sub-specialty after cards, Heme/Onc and Pulmonary/Critical care (look at the bottom of the list and add that to the combined Pulm/Crit Care).

Nephrology is the fourth most popular internal medicine sub-specialty after cards, Heme/Onc and Pulmonary/Critical care (look at the bottom of the list and add that to the combined Pulm/Crit Care). This shows that the 806 patients randomized to ASTRAL dwarves all of the previous work on the subject. (source)

This shows that the 806 patients randomized to ASTRAL dwarves all of the previous work on the subject. (source) The bulk of patients had moderately severe renal disease. It is important that they did not select patients too late in the disease where revascularization may be too late to save the kidney. Similarly you wouldn't wat to intervene too early where the splay between the groups may take longer than 27 months to materialize.

The bulk of patients had moderately severe renal disease. It is important that they did not select patients too late in the disease where revascularization may be too late to save the kidney. Similarly you wouldn't wat to intervene too early where the splay between the groups may take longer than 27 months to materialize.

Most of the patients had severe stenosis, a high grade that if found during a diagnostic angiogram would be followed by an intervention.

Most of the patients had severe stenosis, a high grade that if found during a diagnostic angiogram would be followed by an intervention. The authors emphasized that there was no benefit for the entire cohort but they feel that the therapy is likely helpful for some subset of the population. I agree, like every nephrologist, I have seen patients have dramatic improvements in renal function following angioplasty for RAS. With the immense ASTRAL database it will be exciting to see if the authors can tease out which subgroups benefit from this technology.

The authors emphasized that there was no benefit for the entire cohort but they feel that the therapy is likely helpful for some subset of the population. I agree, like every nephrologist, I have seen patients have dramatic improvements in renal function following angioplasty for RAS. With the immense ASTRAL database it will be exciting to see if the authors can tease out which subgroups benefit from this technology. One of the biggest stories coming out of Renal Week 2008 was this abstract which linked kidney stones to the development of CKD. This is an important study but I filed it under "no duh." Patients with kidney stones tend to be heavier, have more hypertension, get episodes of acute renal failure and have repeated instrumentation on the kidneys. They also have gout, and associated hyperuricemia, an increasingly important progression factor for CKD and hypertension.

One of the biggest stories coming out of Renal Week 2008 was this abstract which linked kidney stones to the development of CKD. This is an important study but I filed it under "no duh." Patients with kidney stones tend to be heavier, have more hypertension, get episodes of acute renal failure and have repeated instrumentation on the kidneys. They also have gout, and associated hyperuricemia, an increasingly important progression factor for CKD and hypertension.[F-FC202] Kidney Stones Are Associated with an Increased Risk of Developing Chronic Kidney Disease

Andrew Rule, Eric Bergstralh, L. Joseph Melton, Xujian Li, Amy Weaver, John Lieske Nephrology, Mayo Clinic; Health Sciences Research, Mayo Clinic

Background: Kidney stones lead to chronic kidney disease (CKD) in patients with rare genetic diseases (e.g., primary hyperoxaluria), but it is less clear if kidney stones are an important risk factor for CKD in the general population.

Methods: A cohort of all Olmsted County, MN residents with incident kidney stones in the years 1984-2003 were matched 3:1 to controls in the general population based on index date (first stone diagnosis for stone formers and any clinic visit for controls), age, and sex. Diagnostic codes (yrs: 1935-2007) and serum creatinine levels (yrs: 1983-2006) were captured with the linkage infrastructure of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Risk of incident chronic kidney disease was assessed using clinical diagnostic codes, end-stage renal disease (dialysis, transplant or death with CKD), sustained (>90 days) elevated serum creatinine (>1.3 mg/dl in men, >1.1 mg/dl in women), and sustained estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Proportional hazards models adjusted for age, sex, and baseline and time-dependent co-morbidities (diabetes, obesity, gout, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, alcohol, tobacco, coronary artery disease, heart failure, cerebral infarct, and peripheral vascular disease).

Results: After excluding persons with prevalent CKD, 4424 stone formers and 10995 controls were identified with a mean follow-up of 8.4 and 8.8 years, respectively. Stone formers had an increased risk of developing a clinical diagnosis of CKD [hazard ratio (HR)=1.6, 95% CI: 1.4-1.8, see figure], end-stage renal disease (HR=1.4, 95% CI: 0.9-2.2), a sustained elevated serum creatinine (HR = 1.4, 95% CI: 1.2-1.7), and a sustained reduced eGFR (HR = 1.4, 95% CI: 1.2-1.6).

Conclusions: These data argue kidney stones to be an important risk factor for chronic kidney disease.